Manifeste : Écrit public par lequel un chef d’État, un gouvernement, un parti, une entreprise etc., rend compte de son mandat ou expose son programme, son point de vue.

Début 2023, BAARS introduit un nouveau projet clef dans son développement, au croisement de nos origines parisiennes, notre culture architecturale et notre savoir-faire unique. Il se nomme : « Manifeste ».

Sur le fond, c’est une vitrine et un hommage à notre fabrication locale, une déclaration d’amour pour Paris et plus spécialement pour le Centre Pompidou. Sur la forme, Manifeste annonce la direction artistique de BAARS pour les années à venir. Elle se caractérise par un travail sur les textures mates, brillantes et sur les volumes. Manifeste sera présenté pour la première fois à OPTI 2023, à Munich. Le début de son histoire remonte à la fin du XIX siècle, ici, à Paris.

In early 2023, BAARS will introduce a new key project in its development. At the crossroads of our Parisian origins, our architectural culture and our unique know-how, this project is called Manifeste. In terms of concept, it is a showcase of and a tribute to our local craftsmanship, a love letter to Paris and more specifically to the Pompidou Centre. In form, Manifeste outlines BAARS’ artistic direction for the years to come. Of note, is the extensive thought given to matt and glossy textures, as well as volumes. While Manifeste will be presented for the first time at OPTI 2023 in Munich, its history starts at the end of the 19th century, here in Paris.

1891 /

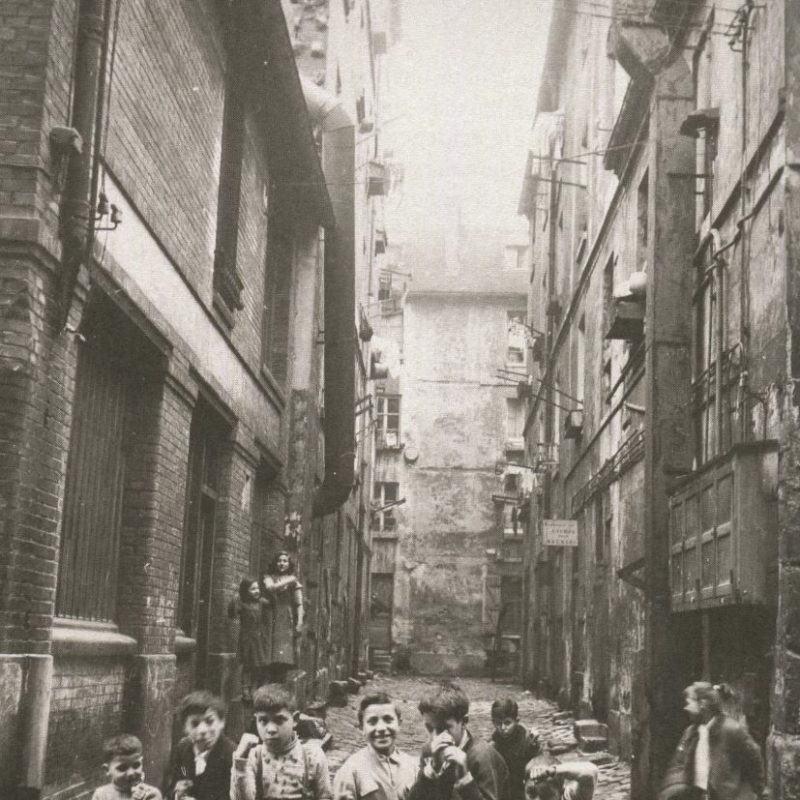

Après l’annexion de ses faubourgs et l’exode rural, Paris voit sa population exploser. Elle compte désormais plus de 2,5 millions d’habitants.

L’étroitesse des voies de circulation par rapport à la hauteur des immeubles et la phénoménale densité de population dégradent fortement la propreté de Paris. La tuberculose se propage.

Dans ce contexte difficile, Paul Juillerat, alors chef du service d’hygiène de la capitale, finalise son enquête sur les conditions de vie en son sein. Ses conclusions sont accablantes et donnent lieu à un concept nouveau : l’identification de zones appelées « îlots insalubres », nécessitant une attention toute particulière.

Nous sommes alors début 1900 et leur nombre s’élève à six. Il ne fera que monter pour atteindre 17 au moment où la Première Guerre mondiale éclate. Malgré des conditions de vie désastreuses, leur réfection traîne.

After the city annexed its suburbs and after the rural exodus, the population of Paris swole to over 2.5 millions. The narrow width of the streets in relation to the height of the buildings and the phenomenal population density severely increased the squalor of Paris. Tuberculosis is spreading like fire.

In this difficult context, Paul Juillerat, then head of the capital’s hygiene department, completed his investigation into the living conditions in the city. His conclusions were overwhelming and gave rise to a new concept: the identification of areas called “îlots insalubre” (“unsanitary islets”) which called for an urgent solution. At the beginning of 1900, there were six of them. This number would increase to 17 by the time the First World War broke out. Despite the disastrous living conditions, their rehabilitation lagged behind.

1969 /

Grand saut en avant : Georges Pompidou vient d’être élu président. Les évènements de mai 1968 viennent tout juste de se terminer et un vent nouveau, une envie de rupture et de créativité flottent sur la capitale. Pompidou, passionné d’art moderne, lance l’idée de créer un centre culturel dans Paris. Il s’inspire du succès d’initiatives similaires aux États-Unis et énonce sa vision : « Un lieu de création, où les arts plastiques voisineraient [sic] avec la musique, le cinéma, les livres, la recherche audiovisuelle ».

Pour son implantation, le lieu est vite trouvé : le plateau Beaubourg, à l’une des extrémités du quartier du Marais. Là où se tenait l’îlot insalubre n°1, rasé dans les années 30, se trouve alors un gigantesque parking sauvage.

Fast forward to 1969 when Georges Pompidou was just elected President of France. The events of May 1968 recently ended and a wind of change, a desire for a break with the past and for creativity, was blowing through the capital. Pompidou, who was passionate about modern art, launched the idea of creating a cultural center in Paris.

Inspired by the success of similar projects in the United States he set out his vision: “a place of creation, where the plastic arts would rub shoulders with music, cinema, books and audiovisual research”. To house such a center, everyone quickly agrees on the location of the former unsanitary islet number one. Destroyed in the 1930s, in its stead was now a gaping hole in the middle of Paris, in the so-called “Plateau Beaubourg”. What would later become one of the bustling ends of the Marais district was then just a large car park.

Pour la réalisation de l’ouvrage, un concours international d’architecture présidé par Jean Prouvé est lancé. Le cahier des charges : créer un bâtiment qui devra répondre aux exigences de pluridisciplinarité, de libre circulation et d’ouverture des espaces d’exposition. Des 681 candidatures émises, deux noms ressortent vainqueurs : Renzo Piano et Richard Rogers, respectivement 34 et 38 ans.

Leur proposition est aussi clivante que novatrice. Elle se constitue d’une part d’une grande place, appelée piazza, en référence à sa source d’inspiration : le Forum Romain. D’autre part, du bâtiment en lui-même, transparent et ouvert sur la ville.

La part belle est laissée au contenu plutôt qu’au contenant. Est imaginée une construction composée de grands plateaux libres et modulables pour répondre aux besoins des expositions, à l’extérieur desquels sont relayés tous les éléments mécaniques et techniques.

Poteaux, gerberettes, gaines de ventilation, accès… tout ce qui est habituellement caché se présente là, aux yeux de tous. Pour aller plus loin encore et quitte à frôler la provocation, chaque élément reprend un code couleur fort : les tuyaux pour la ventilation sont bleus, ceux pour l’eau, verts. L’électricité et la circulation des personnes se voient attribuer respectivement le jaune et le rouge. Cerise sur le gâteau, la rampe d’accès aux étages qui traverse toute la façade du bâtiment deviendra le logo du centre !

An international architectural competition, chaired by Jean Prouvé, is launched for the construction of the center. The specifications: to create a building that would meet the needs for multidisciplinarity, free circulation and open exhibition spaces. Of the 681 applications submitted, two names emerged as the winners: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, aged 34 and 38 respectively. Their proposal is as disruptive as it is dividing.

It consists of two parts: a large square, called piazza, in reference to its source of inspiration, the Roman Forum. And the building itself, designed to be transparent and open to the city.

The emphasis is on the content rather than the container. The construction is made up of large, modular, free-standing platforms to suit the needs of the exhibitions, while all the mechanical and technical elements are displaced outside the building.

Poles, beams, ventilation ducts, accesses… everything that is usually hidden is out there for all to see. To go one step further, bordering on provocation, it is decided that each element will have a strong color code: the ventilation pipes are blue, the water pipes are green. Electricity and the circulation of people will be respectively yellow and red. The icing on the -cake is that the access ramp to the floors, an element that runs diagonally across the entire facade of the building, will become the center’s logo!

/

/

2023 /

S’il fut un temps surnommé « Notre-dame-des-tuyaux », le centre Pompidou constitue aujourd’hui un élément-clef du paysage architectural et un lieu cher au cœur des Parisiens comme des touristes. Et si l’extérieur peut paraître confus et dense, l’intérieur est d’une évidence surprenante : la clarté et la liberté des espaces flattent chaque œuvre qu’ils abritent.

Once nicknamed the “Notre-Dame of pipes”, the Pompidou Centre is today a key element of the architectural landscape and a place dear to the hearts of Parisians and tourists alike. While the exterior may seem confusing and dense, the interior is surprisingly obvious: the clarity and freedom of the spaces flatter the works they house.

C’est cette sublime leçon de pensée qui nous a inspiré Manifeste. En miroir au centre Pompidou, elle met en avant ce qui d’habitude est caché : notre procédé de fabrication.

La justesse et la finesse du dessin original ainsi que les traces d’usinage sont habituellement gommées lors du passage aux tonneaux. Les angles laissent place aux courbes dans la recherche de la brillance parfaite.

Face intérieure et branches sont polies. Elles accueillent le porteur et garantissent un confort sans concession. L’extérieur lui, est brut. Les transitions sont traduites en arêtes. Les angles sont exagérés, les volumes sont repoussés. Les surfaces non polies sont mises en avant et donnent toute sa force à Manifeste : la fabrication et la technique en exposition.

L’ensemble est un objet fonctionnel et minimaliste qui s’inscrit parfaitement dans l’ADN BAARS. Il exprime avec force la conviction que nous partageons avec l’architecte Louis Sullivan : la fonction avant la forme. Ou plutôt : la forme au service de la fonction.

Manifeste se décline en deux formes : l’une papillonnante et l’autre pantos « crown » nommées respectivement Renzo et Richard. La boucle est bouclée.

This sublime lesson in thinking inspired us a new collection, called Manifeste. Mirroring the Pompidou Centre, it brings to the front what is usually hidden.

The finesse of the original design and the traces of machining are usually lost in the barrel tumbling process. Angles give way to curves in our quest for the perfect luster.

The Manifeste project is designed as a showcase for our exceptional know-how: the inner face and the temples are polished. They soothe the user and guarantee uncompromising comfort.

The outer surfaces are rough. The transitions are sharpened into edges. The angles are exaggerated, the volumes are pushed back. A bold aesthetic choice, unpolished surfaces are put forward like trophies giving Manifeste all its strength: a skillful display of manufacturing technique.

The sum is an object that remains functional and minimalist and which fits perfectly into the BAARS DNA. It strongly expresses the conviction we share with architect Louis Sullivan that function comes before form. Or rather that “form follows function”.

Manifeste is available in two shapes: one butterfly and the other crown pantos named respectively “Renzo” and “Richard”. We have come full circle.